Philosophy and Ordinary Life

The actual world had asked something of him. But he lived in the true world and had failed to answer the call.

It was early afternoon. We were young and we were in love.

We walked through the park, long avenues lined with chestnut trees, a clearing with a fountain, heroin junkies and their dogs strewn on benches like wild flowers, magnolias bursting into magnificent, abundant bloom. We kissed, we smiled, we looked at each other, we looked away.

“I want to tell you something,” I said.

-

In Twilight of the Idols, Nietzsche has a short essay - a few numbered sentences, really - called “How the ‘True World’ Finally Became a Fable”.

And what is the true world?

“A true world is a destination; a destination such that to reach it is to enter (or perhaps re-enter) a state of ‘eternal bliss’, a heaven, paradise or utopia.”

The most obvious example of a true-world philosophy is religion: the point of earthly existence is that it leads to the Christian heaven, or to nirvana (the cessation of all suffering), or to moksha (release from the cycle of death and rebirth).

This life, this world - they are not nothing, they may even be valuable: but they are always aiming at something beyond themselves. Our redemption is somewhere else.

Religion is just an example, though. The true-world philosophy is everywhere.

It’s in spirituality of all kinds, because what after all is “enlightenment” other than a destination, such that reaching it is to enter eternal bliss?

It’s in our constant deferral of living, in our belief that life will truly begin once we are rich / in love / done with our studies / in a different job.

It’s there in the constant, relentless dissatisfaction with our lives, our bodies, our partners, our thoughts, our feelings, in the vague sense that this is not it, and that real life is somewhere else.

That’s the basic belief of true-world philosophy: real life is somewhere else.

Over the rainbow, beyond the horizon, there, just there, just beyond reach - there is where we will find true love, true wisdom, true everything.

-

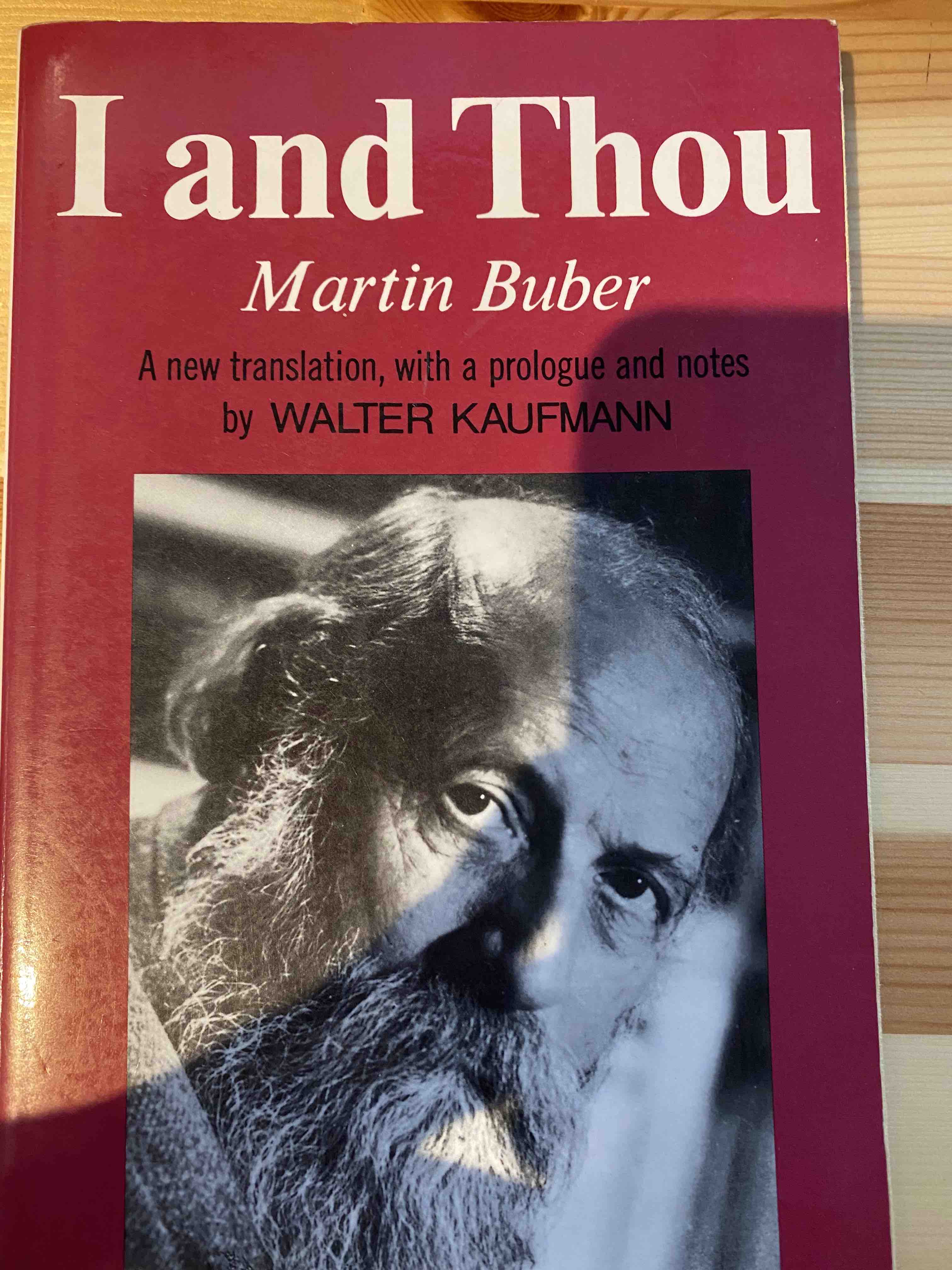

Many of you will have heard of Martin Buber. For those who haven’t, quickly: Buber was a Jewish theologian, a mystic and a philosopher, a Zionist, a writer, a teacher. He grew up in late-19th century Vienna and died in Jerusalem in 1965: a simple sentence that somehow encapsulates the great facts of the 20th century.

The young Martin Buber was a thoroughgoing true-worlder. He writes of his ecstatic mystical experiences, describing them as:

"Hours that were taken out of the course of things. From somewhere or other the firm crust of everyday was pierced … “religious experience” was the experience of an otherness that did not fit into the context of life … the “religious” lifted you out. Over there now lay the accustomed existence with its affairs, but here illumination and ecstasy and rapture held without time or sequence.”

One morning, Buber had one of these religious experiences. Shortly afterwards, an unknown young man came to visit him. Buber was still occupied by the experience, but he was nonetheless polite and attentive, listening closely and speaking openly.

Later, Buber learned from one of the man’s friends - the man himself was dead - that the man

“had come to me not casually, but borne by destiny, not for a chat, but a decision. He had come to me; he had come in this hour. What do we expect when we are in despair and yet go to a man? Surely a presence by means of which we are told that nevertheless there is meaning.”

Buber had not been present. He was there, but not fully. Some part of him was with the religious experience, with the ecstasy and the illumination and the rapture.

The actual world had asked something of him. But he lived in the true world and had failed to answer the call.

“Since then,” writes Buber, “I have given up the “religious” which is nothing but the exception, extraction, exaltation, ecstasy; or it has given me up.”

Since then, says Buber, there is no true world for him. There is only this world. If there is mystery, it is here; if there is eternity, rapture, illumination, it lives here, in the moments and meetings that make up our lives.

Since then, says Buber,

“I know no fullness but each mortal hour’s fullness of claim and responsibility.”

-

“Philosophy” is a big word, isn’t it? Bearded sages, black roll-necks in Parisian cafes, filterless Gauloises, big, profound thoughts about the things that really matter.

I don’t know about the beards and the roll-necks, but the second half of that is absolutely true.

Philosophy is about big things, about Love and Beauty and Truth, about Meaning, about God, about what really matters and how we should live.

But how do you eat an elephant? One bite at a time, said Desmond Tutu, and this is how I think we should approach the big things that philosophy deals with.

We approach them in each moment of our lives, in each meeting, in each encounter with ourselves and the world.

We approach them in this world - in the everyday, out of which we should never be taken.

And this is why I’m going to write about ordinary life at The New Philosophy. I’m going to write about the things that we think are too common or personal for philosophy. I’m going to write about the life that I sometimes think of as too boring and ordinary to write about, but is still the only one I have.

If there’s a God, He must come meet me here. I no longer wish to travel.

-

“I want to tell you something,” I said again.

She waited (and isn’t it wonderful to be waited for like this, to be waited for in the sure, happy certainty that whatever you are about to say will be received with love, that it will be taken in the best possible light, that it will be welcomed and made at home?).

“In every other relationship,” I said, “I’ve always had a little bit of me out,” I said. “Some part of me wasn’t there, it was somewhere else.”

We walked a bit further.

“In everything in my life,” I said, “it’s been like that. Always. Something had left, or something was keeping itself ready to leave. Do you know what I mean?”

“I think so,” she said, and her eyes were soft.

“Well, this is different,” I said. “I’m fully in. All of me, 100%. All of me is saying yes to you and to us and not even my little toe is outside.”