Socrates

He was the son of a stonemason and a midwife.

Neither rich nor poor, neither aristocratic nor a peasant … every year, thousands of boys like him were born to thousands of parents in Athens, and every single one of them would live their ordinary lives and die their ordinary deaths, unknown beyond their own neighbourhoods.

He was a little strange, though. A little awkward, like the pieces wouldn’t quite fit. An average boy, an unremarkable boy, a boy blessed with nothing beyond life … but something about him was just a little odd. The type of boy you could play with well enough, but all the while there would be the slightest hint of something disconcerting. Something in the eyes, or perhaps it was in the calm, undramatic insistence on doing things his way … either way, something was a little uncanny.

They didn’t talk of such things in those days. But if anyone had raised it with him, he would have agreed. He felt strange. The world seemed alien to him, uncanny, somehow mysterious. And the most mysterious thing of all was how everyone else seemed to navigate it so smoothly. The rules, the laws, the Gods … everything was set up so neatly and everyone was so damned certain about everything.

He didn’t feel certain of anything. He felt confused, as a boy will in a world for which he isn’t made.

Later, much later, in a smoky bar in the foothills of Mount Olympus, he had run into a quiet Algerian called Albert who had chain-smoked and talked quietly about something he called “The Absurd”. That was exactly what he had felt as a boy, he realised. But he hadn’t known the word then, and the limits of our language mean the limits of our world.

And then there was that damn voice. That strange bloody voice which he heard, speaking to him, telling him, no, don’t do that! And there was no disobeying that voice. If you heard it, you would understand. It wasn’t fear, the voice wasn’t scary. It was … it was the voice of something real. You couldn’t argue with it, just as you couldn’t argue with a tree. It was just there. Once you saw it, once you heard it, you couldn’t tell yourself you hadn’t. It was just bloody there.

The years passed, as they are wont to do. Around him, the young boys he had played, laughed and fought with grew up. They began to put away childish things, they took wives and fathered children, they entered into the life of the city and the professions of their fathers.

The boy tried. He married Xanthippe, he fathered children. But it is difficult to consistently pretend to be someone that you are not, and every so often, in ways both large and small, he would rebel.

He refused to take his father’s profession. Stonemasonry was fine, he said, a fine thing, even a noble thing, and he yielded to no one in his appreciation of what stonemasons had done for society. If he were lucky enough to be someday blessed with sons - someone whispered, you already have sons, but he moved smoothly past the interruption - then no one would be prouder than him were they to become stonemasons.

But he was not going to become a stone mason.

Fine, they said. You always were a pigheaded obstinate mule. Fine. What will you do instead?

I will, he said, learn how to live.

What?

I will learn, he said, how a man should live.

Sorry, what?

I will learn, he said, a little impatient now but still clinging as best he could to the dignity of his ringing tones, I will learn how a man should live. I will go to the marketplace and ask men: How do you live? Why do you live that way? I will ask them if they know how a man should live and if they do I will ask them to teach me.

His family looked at each other. Finally, Xanthippe sighed, then shrugged.

Fine, she said. It’s porridge for breakfast. I’ll leave it out.

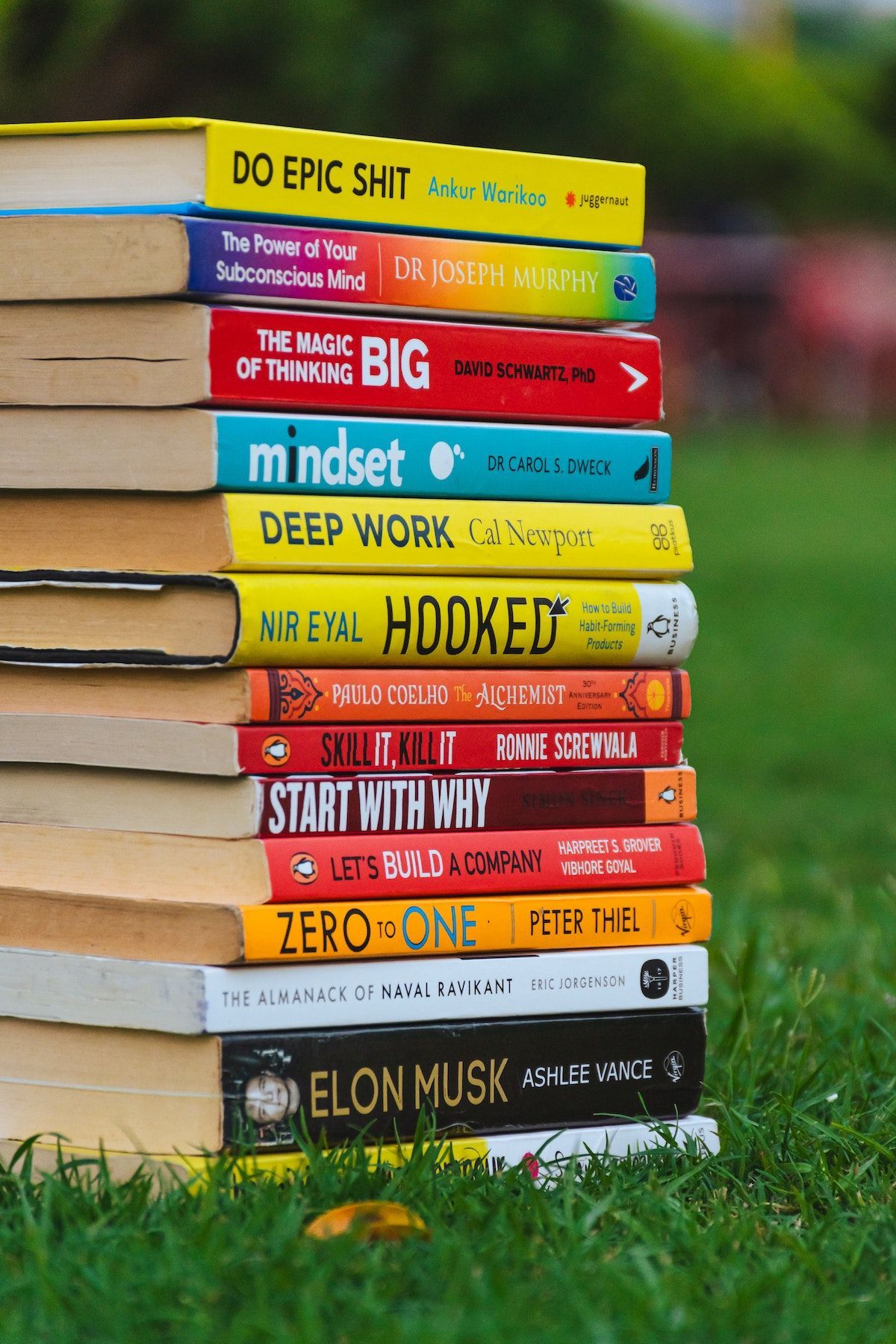

If you think Twitter is opinionated you should have been around in Athens circa 500 B.C. You couldn’t walk more than a few feet without stubbing your toe against a man promising to teach you how the world really worked.

Come, they would whisper into your ear. Come here, come with me, and I will let you in on the big secret, the one piece of knowledge that will blow your mind, the one thing that you need to know, come and let me teach you how to be rich, happy, wise, fulfilled, in touch with God … everything!

Payment in advance, please. You understand … I do this because I love you, because it’s my passion and my purpose to help human beings … but, you know, we all have to live, right? And, anyway, who are you to judge the motives and the actions of the wise? Once you’re enlightened, you will understand.

Now come, let me enlighten you - and today, just for you, I’ll throw in my other course - The 10 Secrets of the Great Warrior Achilles That Will Change Your Life Forever - absolutely free.

Come, my friend, let me help you.

And off they went, the youth of Athens, opening their wallets wide and their hearts even wider, searching, longing for the thing that would make sense of their tumultuous world, for a salve for their suffering, for a cure to the whole damned business of being human.

And there they stood, the serried ranks of the teachers of wisdom, elbows working, scooping up the pain and the longing, taking youthful dreams and eternal suffering and turning them into cold, hard cash.

Socrates went down to the marketplace and spent drachmas he didn’t have on the teachers, on the men who promised wisdom and enlightenment.

He listened to Anaxagoras, who taught that it was nous (mind, intellect, spirit) which set the world in motion; he chatted with Thrasymachus, who said that justice was a sham and that might was right; he had an extended and unusually courteous discussion with Protagoras, the former porter who had made a fortune out of teaching philosophy, who claimed that man is the measure of all things; he had a rather more heated exchange with Callicles …

One could go on forever; and sometimes, it felt to Socrates like it did, because teachers of wisdom are not normally distinguished for their brevity. But Socrates really wanted to know how to live and so he listened, summoning the powers of absorption for which he was famous, listening so closely that it made those he was listening to uncomfortable.

Somewhere, thought Socrates, somewhere, in some moment, with someone, he would find the pearl that would make all the searching worthwhile, the wisdom that would redeem the mockery, the pain, the confusion and the uncertainty.

So on and on he searched.

But answer came there none, dear Reader. You and I might have stopped asking and become management consultants, but Socrates was a different beast. He doubled down on his quest.

Only now, instead of asking the self-appointed purveyors of wisdom, he asked everyone.

Every morning Socrates would eat his porridge, put on his sandals and his toga, and stroll down to the marketplace. On his way, and once there, he would ask anyone unfortunate enough to run into him, How should a man live? What is good? What is valuable?

This got him severely disliked on all sides, a fact which would serious implications later. But a little dislike was not going to stop a man like Socrates. He didn’t even notice it, really. What he did notice, and what did bother him, was that he didn’t seem to be getting anywhere in his search for wisdom. How should he live? What was a good life?

In fact, it wasn’t just that he was getting nowhere. He actually felt more confused than he had been at the start.

It was then that something rather startling happened.

Chaerephon, a boyhood friend of Socrates, had travelled to Delphi. For the Greeks, the centre of the world, the navel of the Universe, was at Delphi. And at the centre of the world stood Apollo’s temple, tended to by his High Priestess, the Pythia, otherwise known as the Oracle of Delphi.

Chaerephon had travelled to Delphi to ask the Pythia a simple question: Who was the wisest of men?

Socrates, she answered

.…

Wut?

Socrates?

Chaerephon liked Socrates. He liked him a lot, actually. He was even prepared to grant that Socrates was of above-average wisdom. But … the wisest of men? Like, no one else was wiser?

Hmm.

When Chaerephon brought this news back, it caused uproar, and nowhere more so than in the heart of Socrates. There was no question for Socrates of doubting the Oracle. Apollo spoke through her and Apollo’s words were true.

But … but … I mean … you know …?

Socrates took a deep breath. It was time for a walk, he decided. No, dear friends, alone, no, that’s quite alright, thank you Chaerephon. I need to be alone for a bit.

The wisest of men.

He, Socrates, was the wisest of men.

He said the words over and over again, each time in a different tone, a different emphasis, like a man trying on hats till he finds one that fits.

Really?

The city walls had long receded behind him. He was out in the country now, where he could not tell and did not care. There were fields. Trees. Green stuff. He saw a rock and sat on it.

The wisest of men, he said, and this time he laughed.

The wisest of men.

Look at me, he thought, suddenly overcome by a spasm of anger. Look at me! He had done nothing with his life. Nothing. He had devoted it all to this mad pursuit of wisdom, to the dream of knowing how a man should live, to the idea of some kind of God … meanwhile, his friends had pursued careers, entered public life. They had won wars, become rich, gathered honours and respect.

And while they had done that, he had walked the streets of Athens, getting fatter with the years, poor, dishonoured, disrespected. That man Aristophanes, that jobbing writer, he had for years been making fun of Socrates, and now there was a play circulating, one in which he was ridiculed even further.

It would have been okay if he had made some progress, he thought. Even a little bit. If he had somehow managed to move one step closer to knowing how to live, to true wisdom. But he hadn’t. He had tried and tried and tried and all he had discovered was the depth of his ignorance. Every step he took, he floundered. Every thing he thought he knew, it turned out he didn’t.

And he was the wisest of men?

He rose, smiling without the faintest trace of happiness. May as well walk back, he thought. Tomorrow is a new day. Maybe it makes more sense then.

It was tomorrow, and it did not make more sense. So Socrates decided to investigate it closely. And the Socratic method is nothing other than a description of how he investigated it.

But before we go into that, let’s clear away a potential confusion. You see, nowadays there are actually two different things that we call the Socratic method. One of these is the safe, non-alcoholic version that is used by teachers, counsellors, coaches, consultants, parents … everyone, really, who is in the business of selling wisdom and wants to somehow do it “interactively”.

In this version, the Socratic figure knows where she wants to lead her interlocutor. She knows the destination - it is to get the student to believe a certain thing, to say a certain thing.

One way she could take the student there is to simply say: hey, you - believe this. Many teachers do that. But another way, the way that its practitioners proudly call Socratic, is to extract the desired belief from the student by asking a series of questions that eventually lead the student to the desired conclusion. (For some reason, this is considered to be more respectful of the student’s independence.)

That’s a very useful method of teaching and it’s fine to call it Socratic. But it’s not what Socrates was up to and it is not what Socrates was after.

Notice, first of all, where Socrates starts from - he starts from ignorance. And not the pretend ignorance of the teacher who actually does know the answer, but actual ignorance. Socrates really does not know.

What do you do when you don’t know something and want to learn it? Well, even today, the most natural answer is - I go and ask someone who does know. And that’s what Socrates did.

So that’s the next step of the Socratic method - if you don’t know something, and it seems as if other people do, go and ask them questions so you can learn the thing you want to know.

At this point, that’s all the Socratic method is. It’s the “method” of asking questions to try to learn something; in Socrates’ case, he asks questions to try to learn about wisdom and how to live.

But it would be a mistake to dismiss this as being “only” about asking questions. Because even at this point, even before I bring in some of the more esoteric and sophisticated stuff, even at this very simple point, there is something remarkable about the method as Socrates himself uses it.

What’s remarkable is the intensity of Socrates’ desire to know. Socrates really wants to know. Most of us would stop somewhere out of politeness or laziness or expedience or boredom or tiredness. Not Socrates. He keeps going and going and going. If there’s a secret to the Socratic method at this point, it’s simply that - Socrates keeps going when most of us would give up.

It’s a useful reminder to us that, sometimes, life isn’t about finding new tricks. Rather, it’s about fully using the trick you already have.

Socrates went first to "one of those who had a reputation for wisdom, thinking that there, if anywhere, I should prove the utterance wrong and should show the oracle “This man is wiser than I, but you said I was wisest.”

He talked with this man, he examined him, and he concluded that the man was not actually wise.

So then he went to another one of those with a reputation for wisdom, and conducted the same kind of inquiry. There too, he found that the reputation was unearned.

Then he went to another, and another, and another still, and he kept finding the same thing: none of these men were actually wise!

Then, having exhausted the “public men”, Socrates went to the poets and then to the hand-workers, and in both cases, in all cases, he continued to be disappointed. These men, who thought themselves so wise, were not wise at all!

From these continued disappointments, Socrates eventually generates an answer to the riddle of why the oracle had called him the wisest of men. The point, says Socrates, is not that he, Socrates, knows more than other men.

Rather, "it is likely that the god is really wise and by his oracle means this: “Human wisdom is of little or no value.” And it appears that he does not really say this of Socrates, but merely uses my name, and makes me an example, as if he were to say: “This one of you, O human beings, is wisest, who, like Socrates, recognises that he is in truth of no account in respect to wisdom.”

And from here, we can move to version number 3 of the Socratic method.

But let’s begin with a recap.

Version 1 of the Socratic method is when the Socrates figure knows where she wants to take her interlocutor. She already knows the conclusion that she wants to reach, and uses cunningly designed questions to make her student reach the desired conclusion.

Version 2 of the Socratic method is when the Socrates figure truly does not know. She does not know what the true conclusion is, she has no prior destination in mind. But she knows that she does not know, and she wants to learn what she does not know, so she goes to people who say they know what she wants to learn and asks them questions.

Version 3 … this is a little bit more esoteric, perhaps. The aim of the Socratic method in Version 3 is neither to learn something nor to make the interlocutor arrive at some belief. Rather, the aim is to bring the interlocutor to a realisation of their ignorance. It is to bring the student to the point where she recognises just how ignorant she truly is, just how little she truly knows.

What could be the point of that?

Well, perhaps Socrates is telling us that one of the biggest obstacles to wisdom is thinking that we already have it.

Perhaps before we can build, we need to destroy (this is an idea we will encounter later too, because it is an idea that always recurs in the history of philosophy).

There is another possibility, much more unsettling than the ones I’ve just mentioned. It’s a theme we will repeatedly encounter, because it is a theme that always arises when human beings try to understand and experience the world.

If we allow it to, the Socratic method drives us to the end of thought. It takes us to the point where we realise: we have danced and sparred, we have spun elaborate castles out of the air, we have built words upon words and laid thought upon thought and … and we can go no further. We, we who thought we were so clever, who were proud of how subtly we can reason and how elegantly we can formulate our thoughts … we must confess: we are lost.

This is one of the methods of Zen Buddhism too. You see it most famously in the koan - try to solve it, try with all your soul to solve it, try try try … and then, when you have reached the end and are fully despairing, when what you call your mind is overturned: then you see the point of it.

In Version 3, the Socratic method is about destroying your mind.

And suddenly, it’s not surprising at all that they killed him.